Home | Articles | Workshops | About | Updates

How not to double

A double hit is when both fencers hit each other at roughly the same time. Doubles are a normal, common part of fencing, and committing them should be considered neither a moral failing, ahistorical, nor more of a tactical failing than any other error. However, it is important to understand how to minimize preventable doubles, because they are not an ideal outcome. Additionally, many HEMA rulesets disproportionately punish doubles in terms of pool standings, and/or punish both fencers harshly when one is committed, for example declaring a loss for both fencers when three doubles are committed.

It is important to understand that everything written here should be taken as rules of thumb at most, and not hard and fast rules, nor magic spells that will make doubles disappear from your fencing. Doubles are a fact of fencing, and it is impossible to completely remove them from the game without drastically changing it to the point that it is unrecognizable.

Throughout this essay, I have avoided using the word “safe” in reference to any kind of fencing action. To me, the idea of “attacking safely” or any adjacent term implies that there is a way of attacking in which there is no risk of failure. In reality, no matter how sensible, well-planned, or prepared your attack is, there is always a chance that it will end in a double hit or a clean hit against you. Acknowledging this and making calculated risks is an important part of fencing, and in my opinion trying to think about some kind of ideal safe attack takes something away from that.

Part 1: Target

Low attacks

When aiming to reduce doubles, the first thing one should make a note of is where on their opponent’s body they are attempting to land a hit, as some target areas are more likely to result in a double than others. This is the easiest issue to spot, and also the easiest to fix; simply choose to attack other targets.

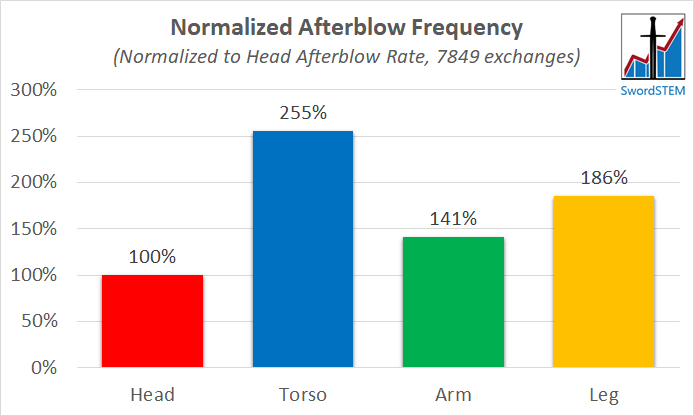

Here is a chart of likelihood of being afterblown for general target areas at Combatcon 2021, taken and compiled by Sean Franklin via HEMA Scorecard:

While this chart does come with some caveats, It is for afterblows, not doubles (there is no data on target area for doubles); one handed strikes were not allowed in this tournament, which often account for many leg hits; there were far fewer leg hits than torso hits recorded in the tournament. it mostly confirms what we can intuitively infer: Lower targets are more likely to get you hit when you go for them. Though I don’t have hard data to back it up, in my opinion this is due to two main factors:

- Low targets (strikes to torso, stabs below chest, strikes to leg) are more difficult to parry,

- Attacking low targets leaves your upper body exposed.

The combination of these two factors means that a defending fencer may be more likely to simply attack the easy-to-reach upper opening than attempt a difficult parry.

This of course doesn’t mean you should never go for those targets. In the correct tactical scenario, it is possible to stab low, strike the torso, or attack the leg and not double or afterblow. It’s just a little bit more difficult, and if you tend to double a lot and also tend to go for those targets, there is a chance that the two may be correlated.

Advice for coaches: It often happens that a beginner will get into a habit of going low simply because it is the only thing that they can actually hit - their high attacks are always parried or avoided, and their low attacks always end in a double, but at least they are hitting you. While I feel that this tends to be a problem that goes away with time and experience, there are some options for dealing with it in the moment. A simple tempting option is to tell them that they are not allowed to do low attacks anymore, but this option is inelegant, and it may leave the fencer thinking that you took away their only viable option because you didn’t want to get hit.

Instead, I prefer to solve this by rewarding high hits and punishing low hits via my fencing. Allow some high hits to get through, and always parry or avoid low hits (they are harder to parry, but if they are a beginner you should be able to do it, and if you can’t, make sure you at least double them). In an extreme case of someone who would only go for low attacks, I have even stayed in a low guard to parry all low attacks, and ate all high attacks. Believe it or not, he got the idea, and even when I switched back to normal fencing, he attacked high targets more often.

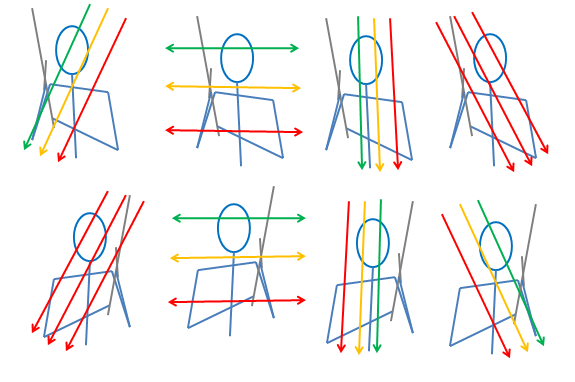

Cutting planes

This is when you are already attacking a target that is less inherently likely to end in a double. When entering with a cut, be it as an attack or a counterattack, be aware of the plane that your cut is making in space. Cutting on a plane that will intersect your opponent’s most likely plane of attack is more likely to block out their attack if you are going for a counterattack, or if they attack unexpectedly. If you are attacking high and still doubling, observe the plane of your cuts and see if they are actually intersecting the opponent’s cuts, and if not, adjust them.

This is particularly pertinent in a right hander vs left hander matchup, in which both fencers have mirrored strong side attacks (left hander starting from their left, right hander starting from their right). In this situation one must either choose a weak side cutting plane, or a horizontal plane in order to intersect the other. This issue is tricky but not insurmountable, but if you wish to avoid it you can simply switch to a point forward guard and attack with stabs instead of cuts.

Part 2: Tactics

Tactical definitions

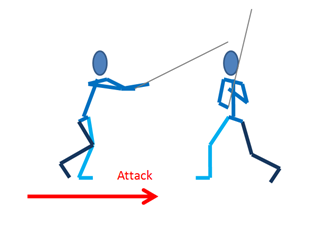

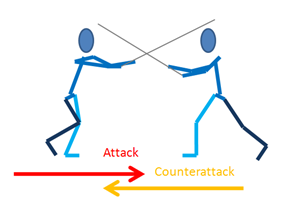

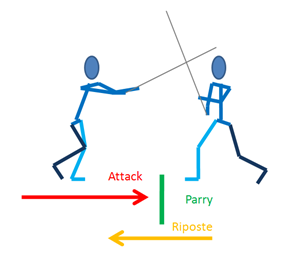

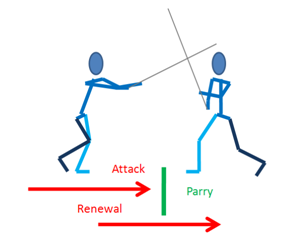

For our purposes, I will define four different tactical concepts: attack, counterattack, parry riposte, and renewal. For different explanation and examples, see this video: https://youtu.be/58tz6t8wx2U

The reason for these definitions is not to inject modern fencing theory into HEMA, but to identify combinations of situations in which a double hit may occur. In order for a double hit to physically occur, both fencers must be attempting to land a hit on each other at the same time. If one fencer is trying to land a hit and the other is not (defending, standing still daydreaming, unarmed, etc), then a double hit cannot occur. Therefore we can identify tactics in which hits are attempted simultaneously, and label them as higher risk situations for a double hit.

|

THEY: YOU: |

Attack | Counterattack | Parry-Riposte | Renewal |

| Attack | X | More double risk (can’t control) | Less double risk | N/A |

| Counterattack | More double risk (can control) | X | (counter time) Less double risk | N/A |

| Parry-Riposte | Less double risk | (counter-time) Less double risk | X | More double risk (can’t control) |

| Renewal | N/A | N/A | More double risk (can control) | X |

Reducing risks

Now that we know where the tactical problem areas are with doubles, we can think about ways to mitigate them. An easy way to avoid doubles would be to simply remove counterattacks and renewals from the game. This type of ruleset can be seen in la canne de combat, and modern FFE lightsabre rules, in which a fencer gains priority by chambering a strike, and the opponent cannot legally attack them while they have priority. Modern foil and sabre also use right-of-way based priority, but it only comes into play after a double hit occurs; it is perfectly legal to counterattack or renew as long as you don’t get hit while you do it. While this does indeed create a fun game with few doubles, it is a very different game than what I am personally interested in playing with longsword. Plus, the historical source that I study (Lew) includes many situations that can be considered counterattacks and renewals. Therefore, though the risk of doubles can’t be entirely eliminated, here are some ideas for reducing the risk of doubling when using a tactic within the problem area.

Attack vs Counterattack: Observe your opponent and try to reconnoiter if they have a preferred counterattack. If so, it may be a better idea to try to provoke their counterattack and deal with it some other way, rather than attacking straight in. Against a beginner or someone who throws chaotic or random counterattacks, it is often better to stay away and punish with non-committal shallow attacks when they open themselves with a wild swing.

Counterattack vs Attack: Accompany your counterattack with either an oppositional element (locking out their blade) or an avoidance movement (dodge or step back). Set up your counterattack by giving your opponent an opening, positioning your sword in a way that limits their viable targets, or reconnoiter where and how they are likely to attack. The more information you have, the more likely you will be able to counterattack without doubling. No matter how well you plan, there is always a chance of doubling when you choose to counterattack. The most likely way to reduce doubles is to cut out counterattacking from your game completely.

Parry riposte vs Renewal: Observe your opponent and try to reconnoiter if they tend to always throw a renewal after being parried. This is a common behavior. If so, there are a few options:

- Attempt to counterattack instead of parry riposte

- Tighten the timing of your parry riposte in order to have time to land the riposte and then defend against the renewal

- Parry in such a way that you can then counterattack or tightly parry riposte the opponent’s renewed attack

- Vary the strength of your parries, from simple guard parries to hard beats, in order to give your opponent a different bind than they expected, and therefore throw off their renewal timing.

- Keep parrying until they get tired of attacking, then riposte (not recommended, highly susceptible to feints or mix-ups)

Renewal vs Parry riposte: As with the previous, reconnoiter if your opponent tends to riposte immediately after parrying. If they often parry without riposting, then it is less risky to attempt to renew your attack. In general, unless you are sure that they will parry without riposting, it is better to take a small amount of time when you bind to assess their next move, or simply expect the riposte and move into a parrying position (or both). It is also possible to renew in a way that locks out or avoids their riposte, for example zwer under zwer, though this is more difficult and requires even more prediction. As with counterattacking, the most likely way to reduce doubles is to cut renewals out of your game completely.

Part 3: Awareness

In order to make any of the advice in the previous section work, it is a prerequisite that one must first know whether they are attacking or being attacked. This is the most difficult part, and also the most important, because you can’t actually implement any of the advice in the previous section if you don’t know that you are counterattacking. There is also no hard and fast rule for knowing all of these things, it is largely based on experience and pattern recognition. However, we can go over some rules of thumb that you can look for.

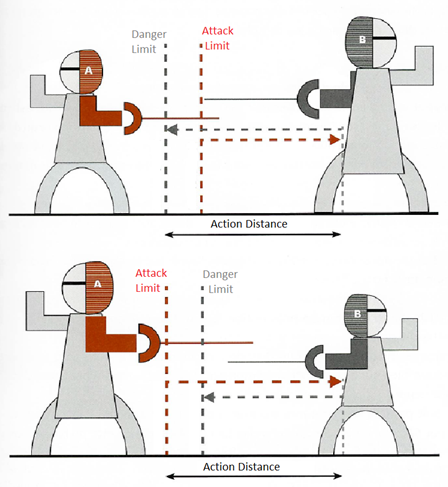

Entering action distance

While fencing, there is always a distance at which a fencer can make an attack that has a chance of landing. This distance is different for everyone, and depends on reach and athleticism (you can find your attacking distance by playing the Direct Attack drill). The distance at which both fencers are within the attack distance of the fencer with the longest reach can be considered the “action distance,” because that is the distance in which a hit can potentially occur. These terms are taken from L’esprit de l’épée by Delhomme, Di Martino, and Carre, and is expressed in the following diagram from that book:

The reason this is important is because in order for a fencing action to happen, one fencer must make the decision to cross into the action distance. While the person entering distance is not guaranteed to launch an attack, entering distance is a good indicator that they intend to do so. Therefore, if your opponent is attempting to cross into the action distance, it is a good rule of thumb to assume the role of the counterattacker.

In simple terms, if someone is walking towards you and you are standing still or backing away, you are probably counterattacking.

Post exchange analysis

While it is often difficult to tell in the moment if your role is attacker or counterattacker, it is often easier to analyze an exchange directly after it happens, with a third party observer helping you, or while reviewing a video. This way you can build pattern recognition and attempt to avoid similar situations in the future.

You may be counterattacking if the following applies to you upon reviewing an exchange that ends in a double:

- They are stepping in with their attack while you are standing still

- They are stepping in with their attack while you are stepping back

- You are making some kind of avoidance movement while attacking

- You step in with your attack, but only after they have stepped in with theirs

A good awareness exercise can be found in The Mental Preparation of Fencers and Others by Aladar Kogler: two fencers fence with a ref, after each score the ref asks the scorer what their opponent was doing and how they responded, and then asks the opponent if the story was correct. Building awareness is an important skill which can help many aspects of your fencing beyond assessing why a double happened.

Part 4: Useful Drills and Games

Direct attack drill

- Rules: A is attacker starting in point high striking guard, B is defender starting in low guard. Neither can move, start in a set spot, A throws a direct strike to the head, B attempts to parry. If A successfully lands a hit, A takes a small step back and repeats. If B successfully parries, A takes a small step closer and repeats.

- How it helps: This helps by allowing you to find your own attack distance and understand the attack distances of others, in order to identify when you or your opponent is making the decision to enter action distance while fencing.

La Canne Inspired Fencing

- Rules: Fencing, but you must chamber a strike in order to claim priority (if both chamber, priority goes to whoever chambered first; if both chamber simultaneously, the exchange may be ruled a simultaneous and thrown out; “chambering” is defined as retracting your blade beyond 90 degree vertical, along with a backward movement of the hands). Priority ends if you hold your chambered position for too long (2 steps, or judge’s discretion if they are standing still), or if your attack misses or is parried. You may only score when you have priority (no attacks in preparation or counterattacks). When a defender parries, priority immediately switches to them, and they may riposte without chambering as long as the parry and riposte are done in a fluid motion.

- How it helps: This game helps fencers identify who is the attacker and when they are counterattacking by making it obvious who the attacker is, and banning counterattacks. Play with a ref so you can call people out for doing illegal counterattacks. This game is also good for practicing indirect attacks and parries.

Sabre March

- Rules: A is attacker, B is defender. Both start in one step distance from each other. A must continue moving forward, and has priority. Goal for both is to land a touch. B loses if they cross the back line, A loses if they step backwards or stop moving forwards, or if they swing and miss. Priority switches to B in the case of a parry riposte, as long as they riposte in one fluid motion. If someone parries and no riposte lands, fence it out until someone lands a touch, with a double being a reset with no points scored.

- How it helps: Because one person is the dedicated attacker and the other the dedicated counterattacker, this teaches the defender to understand the role of a counterattacker, and be careful to hit without being hit if they choose to counterattack instead of defend or avoid.

Part 5: Conclusion

To recap, here is a TL;DR of all things touched upon:

- Be careful attacking low targets

- Cut so that the plane of your cut intersects the plane of their most comfortable cut

- Counterattacking comes with a risk of doubling

- Renewing comes with a risk of doubling

As a reminder, even if you follow all of the advice here perfectly, doubles will still happen. You can only control your opponent to a certain extent, and it’s impossible to account for all possibilities in any given situation. Even if your opponent is also following this advice to the best of their ability, doubles will still happen, because fencing is chaotic. There is nothing inherently special about a double, it is certainly not a moral failing. It is a non-ideal outcome, and should be treated as a learning experience, like all non-ideal outcomes.

It’s like Captain Jean-Luc Picard said, “It is possible to commit no mistakes and still lose; that is not a weakness, that is life.” He said this to Lieutenant-Commander Data, who then went on to frustrate a superior master of a strategy game by forcing a stalemate.

© Stephen Cheney, 2021. Posted with permission of the author.